Operating Working Capital and Supply Chain Bias

This article introduces the concept Supply Chain Bias. It describes what it is, what causes it, and its implications on Operating Working Capital performance.

It also describes 5 common Supply Chain Biases to watch out for, and provides high level insights into how companies can effectively transcend their blind spots.

Key Take Aways

- Supply chain bias refers to the tendency for individuals or organizations to perceive supply chain inefficiencies from a narrow perspective.

- This narrow perspective often focus on localized issues or symptoms. This rather than considering the broader implications for the entire supply chain and Cash Conversion Cycle.

- Supply chain bias can often lead to informal safety mechanisms being put in place. These are often in the shape of Operating Working Capital buffers.

- While these buffers may provide short-term relief, they often won’t address the root causes of inefficiencies or contribute to overall supply chain optimization.

- To address supply chain bias, it’s essential for organizations to encourage a holistic and collaborative approach to supply chain management.

- Companies should invest time and resources to identify and remove their supply chain biases – as part of achieving their Operating Working Capital Setpoint.

What is Supply Chain Bias?

Companies’ individual functions are often inclined towards solutions favoring themselves, with less focus on the carryover effect on neighboring areas of the supply chain.

We call this inclination Supply Chain Bias.

This lack of end-to-end supply chain focus is a common driver of inefficiencies, often resulting in excess levels of operating working capital.

As a result, many companies find themselves operating with more operating working capital than is required to support operations. And without fully understanding their optimal levels to begin with, their Setpoint.

Learn more about the difference between Supply Chain Constraints and Supply Chain Bias – take our accredited e-learning course Managing Working Capital on MyAcademyHub.com!

Distinguishing Between Inherent Supply Chain Constraints and Supply Chain Bias

Supply Chain Constraints refer to the underlying drivers of a company’s operating working capital requirements. Together, these drivers determine the level of operating working capital required to sustain or grow a business.

This optimal level is what we call an Operating Working Capital Setpoint. This Setpoint level can be challenging to find – let alone reach – as it involves multiple stakeholders with often conflicting strategies, targets and KPIs.

These conflicts are not only prevalent in a company’s relationship with its external stakeholders, but internally as well.

Supply Chain Bias on the other hand refers to the tendency for individuals or organizations to perceive supply chain inefficiencies from a narrow perspective. This often focuses on localized issues or symptoms rather than considering the broader implications for the supply chain in full

- By interpreting supply chain inefficiencies through subjective lenses, individuals create their own versions of reality and success criteria

- This narrow focus often leads to a failure to recognize how local efforts to deal with inefficiencies in one area may impact other parts of the supply chain.

- This can in turn result in differing perceptions of what constitutes success within the entirety of the supply chain. making it challenging to align goals and strategies across the organization.

Consequences of Supply Chain Bias

To mitigate these perceived inefficiencies or risks within a specific domain, individuals often implement informal safety mechanisms. Often in the form of operating working capital buffers.

While these mechanisms may provide short-term relief, they often won’t address the root causes of inefficiencies. Nor will it contribute to overall supply chain optimization.

- Focusing on localized inefficiencies and implementing informal safety mechanisms can have implications for overall supply chain performance.

- It may lead to suboptimal decision-making, increased costs, reduced agility. This will ultimately hinder the organization’s ability to compete effectively in the market.

- To address supply chain bias, it’s essential for organizations to encourage a holistic and collaborative approach to supply chain management.

- This involves promoting cross-functional communication and collaboration, fostering a culture of shared responsibility for supply chain performance.

- Also, adopting analytical tools and methodologies that enable organizations to identify and address inefficiencies at the systemic level.

- Additionally, emphasizing the importance of considering the broader implications of decisions and actions within the supply chain can help mitigate bias and drive towards more optimal outcomes.

Implications on Operating Working Capital

The activities and precautions originating from a supply chain bias can often make sense at first or even second glance.

However, the habit of hedging or buffering to offset a symptom rather than solving the underlying problem, tends to have long term negative effects:

- It leaves the problem unsolved and fosters a culture of complacency rather than continuous improvement.

- It creates disturbances to the natural flow of a supply chain, with a negative effect on process stability as well as trust between internal and external stakeholders.

This often results in additional biases piling on each other impacting not only working capital but also service delivery performance and cost. - It builds up “wrong” type and often slow-moving working capital. This takes up space from in-demand high runners, creating an imbalance in the supply chain set-up.

This imbalance reduces flexibility to meet changes to short-term demand. Also, limiting the ability to move quickly and adapt to new market situations. - When left unattended for too long, it often becomes the truth. Most legacy biases are reminiscences of safety- or hedging biases of the past.

The 5 Common Supply Chain Biases

- Incentive Bias. Person incentivized to improve specific performance metrics disregarding effects on the business as a whole.

E.g., a top-down drive for improved DPO made purchasing push standard supplier terms from net 45 days to net 90 days in one go. This led to weakened supplier relationships and a long-term negative effect on supplier pricing and service level. - Safety Bias. Person installing or modifying process buffers to secure own delivery.

E.g., issues with missing input materials, leading to costly over-night deliveries and delayed production starts, made the inventory planning manager increase safety stock levels of missing items, as well as move receipt date ahead of time for future deliveries. - Technical Bias. Person seeking to optimize a specific assets performance, disregarding implications to the larger value chain as a whole.

E.g., in order to reduce in-process waste, engineering recalibrated its equipment to allow for multiple variation SKUs, driving complexity and reduced flexibility (see case example below). - Legacy Bias (also referred to as Confirmation Bias). A person favoring information confirming pre-existing beliefs or holding on to anecdotal evidence and company folklore describing terrible things that have happened in the past when someone tried to make a change, regardless of what current data and logic would say.

- Hedging Bias. Person modifying input planning assumptions to increase likelihood of meeting own priorities.

E.g., more or less frequent issues in production, leading to delayed shipments and some lost orders, made the sales manager over-forecast future demand to increase availability and pick-rate of his/her goods.

Understanding the Setpoint Requirements

To understand and subsequently reach an Operating Working Capital Setpoint, a company must first distinguish its inherent constraints from its supply chain bias.

Then, it must realize and resolve the underlying issues which put the biases and their consequential safety mechanisms in place to begin with. Only then is it safe to strip away the excess operating working capital layers.

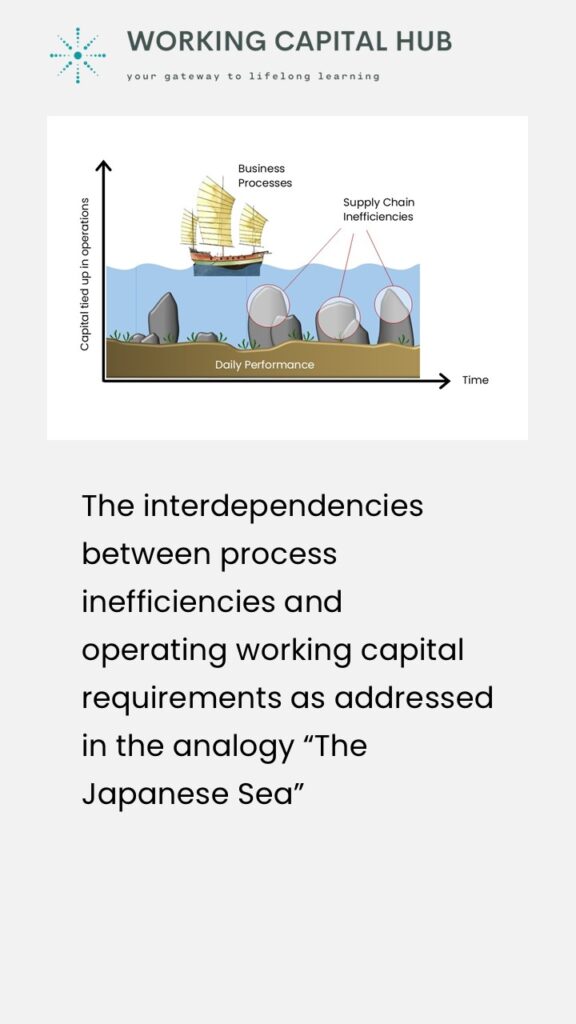

The interdependencies between process inefficiencies and operating working capital requirements were already addressed as part of the original Lean concept and became famous in the analogy “The Japanese Sea”.

- This analogy imagines a boat sailing across an ocean. Below the surface rocks are protruding from the seabed, but if the water level is kept high enough, there is no danger to the boat.

- The boat symbolizes a company’s business processes and the water represents the operating working capital levels maintained to keep the processes moving.

- The bottom of the sea in turn represents the daily performance of the various stakeholders involved in the process, and the rocks your supply chain inefficiencies.

A common interpretation of the analogy suggests a company should start by draining the water. This would expose the underlying inefficiencies – and thus force a problem-solving approach.

However, draining the sea without first reducing or removing the inefficiencies will strand the boat. And how do we react to a stranded boat? We restore the water to its original level – or even higher for extra safety measures.

This is a reason why many companies struggle to maintain operating working capital improvements. They force a reduction before underlying inefficiencies are resolved, often leading to issues with delivery performance, quality, and cost.

Also, if not understanding their Setpoint level, they face the risk of cutting too deep, adding fuel to the fire. The fastest solution to this situation will always be refilling the operating working capital.

Breaking Through the Supply Chain Bias

A relevant checklist to consider when looking to break through your supply chain bias:

- Learn your Setpoint requirements. A company must understand what operating working capital should be there, before removing what shouldn’t.

- Don’t look at the symptoms – focus on the cause. Understand what created the biases to begin with, before trying to improve.

- Align your functions towards one common goal. Many biases are a result of local optimization, without considering the effects on the company as a whole.

However, this is not easy:

- Supply Chain Bias is not always easy to spot. Inefficiencies and their symptoms are often interpreted differently. A bias is subjective by nature, and the person who installed it in the first place might not even be aware it is a bias.

In cases where the person would be aware, there is often an element of mistrust towards the organization’s ability to identify and solve the underlying issue, making him/her less prone to step forward. - Root causes are often hard to identify and resolve. While companies may address “low-hanging fruit,” some issues are complex and time-consuming. Additionally, solutions that benefit the entire supply chain can sometimes negatively impact individual performance metrics.

- It will take time and effort. All the above must be done in parallel to daily operations, on top of an often already full workload – in competition with other pressing initiatives.

It is often not a sprint consisting of a few larger activities, but rather several incremental steps towards a Setpoint. - And note, a Setpoint steady state is not achieved through a few isolated activities, but through multiple incremental steps over time.

Eager to learn more? Check out our accredited e-learning course Managing Working Capital

Leave a Reply