Working Capital and Cashflow – Definition, formula, and application

This article will explain the relationship between Working Capital and Cashflow. It will provide insights into what cashflow is, its three main components, and how changes to working capital affect the operating cashflow.

Additionally, it will provide examples of what causes changes to operating working capital.

Key Take Aways

- Insufficient cashflow limits a company’s ability to perform basic functions such as purchasing goods, paying salaries, investing, growing, or repaying debt.

- Cash is in turn directly affected by how effectively a company can convert its operation working capital into sales and customer payments.

- A company’s operating cashflow is calculated as: operating profit + depreciation & amortization +/- changes to operating working capital.

- An increase in operating working capital has a negative effect on cashflow as this means more cash is tied up in operations.

- Conversely, a decrease has a positive effect on cashflow, as this means less cash is used to finance the operating working capital.

- Managing working capital effectively is crucial for optimizing cashflow.

- Balancing the levels of accounts receivable, inventory, and accounts payable, along with controlling operating expenses, helps ensure that a company maintains adequate liquidity to support its operations and growth initiatives.

Why is Working Capital and Cashflow important?

Without generating enough cashflow, a company will find it difficult to conduct routine activities such as buying goods and services, paying its employee salaries, making investments, financing growth, or paying off debt.

Cash is in turn directly affected by a company’s ability to convert its operating working capital assets into sales and customer payments.

Note that companies can show a profit on their income statement while still running out of cash due to differences in the timing of cash inflows and outflows. These differences will show up on a company’s balance sheet as working capital.

What is Cashflow?

A company’s cashflow is the net amount of cash being transferred in and out of a company in a period. It is described in the company’s cashflow statement.

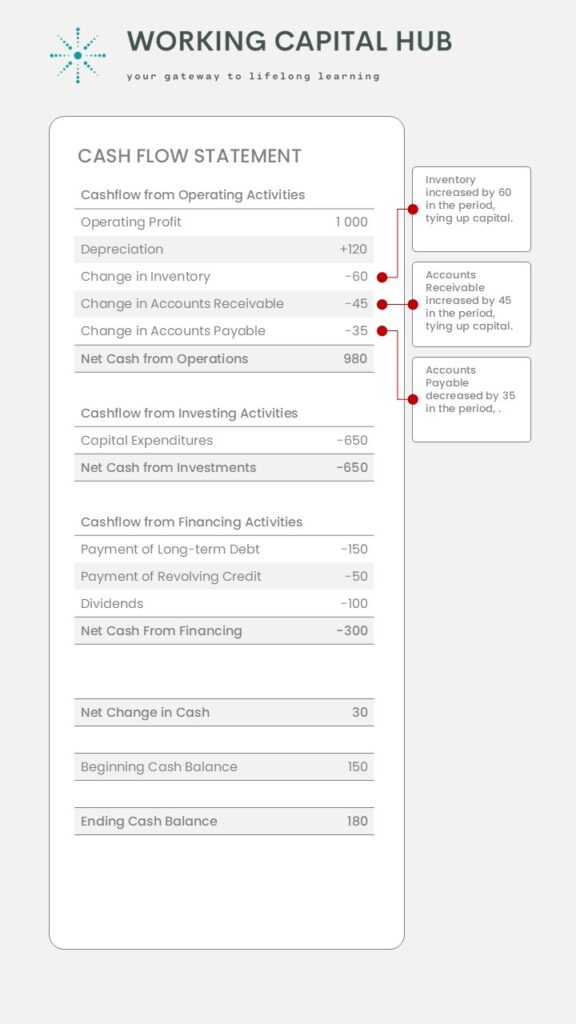

Understanding the cashflow statement is essential for assessing and evaluating a company’s liquidity, flexibility, and overall financial performance. The cash flow statement is in turn divided into 3 sections:

- Cashflow from operating activities: the first section include a company’s cash movements generated by its normal day-to-day business operations. This is where you find changes to operating working capital.

- Cashflow from investment activities: the second section include a company’s cash movements resulting from purchase or sale of property, plants, equipment, or long-term investments.

- Cashflow from financing activities: the third section include a company’s cash movements resulting from loans, purchase or issue of own stock, and dividends to shareholders.

The relationship between Working Capital and Cashflow

Operating working capital refers to the current assets and liabilities a company uses to effectively run its day-to-day operations (read more about operating working capital here). However, these assets cost money to acquire and maintain.

Whenever a company increases its operating working capital – by purchasing more inventory, extending credit to customers, or delaying payments to suppliers – it ties up cash that could otherwise be used for other purposes. This reduces immediate cashflow.

Conversely, reducing operating working capital – by collecting receivables faster, managing inventory efficiently, or negotiating better payment terms with suppliers – can free up cash. This in turn improves cashflow.

Therefore, the relationship between operating working capital and cash flow is that efficient management of operating working capital directly impacts the company’s liquidity and ability to generate cash.

The formula for calculating cashflow from operating activities is therefore:

Operating Cashflow = Operating profit + Depreciation and Amortization +/- Changes to operating working capital

What causes changes to Operating Working Capital and Cashflow

Changes to Inventory

- Increase in inventory – When inventory levels rise, more cash is tied up in unsold goods. This decreases cash flow.

- Decrease in inventory – Lowering inventory levels frees up cash as less money is tied up in goods. This increases cashflow.

Changes to Accounts Receivable (AR)

- Increase in AR – If accounts receivable increases, it means that more sales have been made on credit or not paid in time, resulting in cash not yet received. This reduces cashflow.

- Decrease in AR – If accounts payable decreases, it means that more cash has been collected from customers from previous credit sales, resulting in increased cashflow.

Accounts Payable (AP)

- Increase in AP – If accounts payable increases, it indicates that the company has prolonged its payment terms or otherwise delayed payments to its suppliers, conserving cash. This increases cashflow.

- Decrease in AP – A decrease in accounts payable means that the company is paying its suppliers more quickly, reducing cashflow.

Learn more about Working Capital and Cashflow! Check out our accredited e-learning course: Managing Working Capital

Why does Operating Working Capital change?

Changes in operating working capital can occur for many reasons, e.g.,

- Due to changes to market, customer, or product mix. For example, a company moving into regions with innately longer customer credit terms will experience an increase in its accounts receivable.

Alternatively, a company increasing its share of long-distance suppliers will experience longer replenishment lead times, with higher inventory levels as a direct result. - Due to changes in operating efficiency. Higher operating working capital is often a consequence of supply chain inefficiencies. For example, a company that experiences issues with its supplier delivery performance might increase safety stock levels to ensure availability.

Alternatively, a company experiencing deteriorating internal quality control might experience an increased level of customer complaints and disputed invoices. This would in turn result in delayed payments and higher accounts receivable as a direct result. - Due to seasonal fluctuations in business operations. For example, retailers may experience higher inventory levels during peak seasons, leading to a temporary increase of cash tied up operations.

Likewise, producing companies with temporary capacity constraints will build up their inventory reserves. These spikes in demand will also impact both accounts receivable and accounts payable in the period. - Due to growth. Growing companies will require additional working capital to support its operations. For example, a company growing 20% in sales will see its operating working capital grow 20% (or more), assuming no changes to its inherent supply chain conditions and constraints.

Note that companies with insufficient control will often experience an exponential increase in their operating working capital when growing.

In summary, operating working capital and cashflow are closely intertwined aspects of a company’s financial management.

Efficient understanding and management of working capital drivers are crucial for optimizing cash flow, supporting operational needs, and ensuring the overall financial health of the business.

Example how changes to Working Capital affect Cashflow

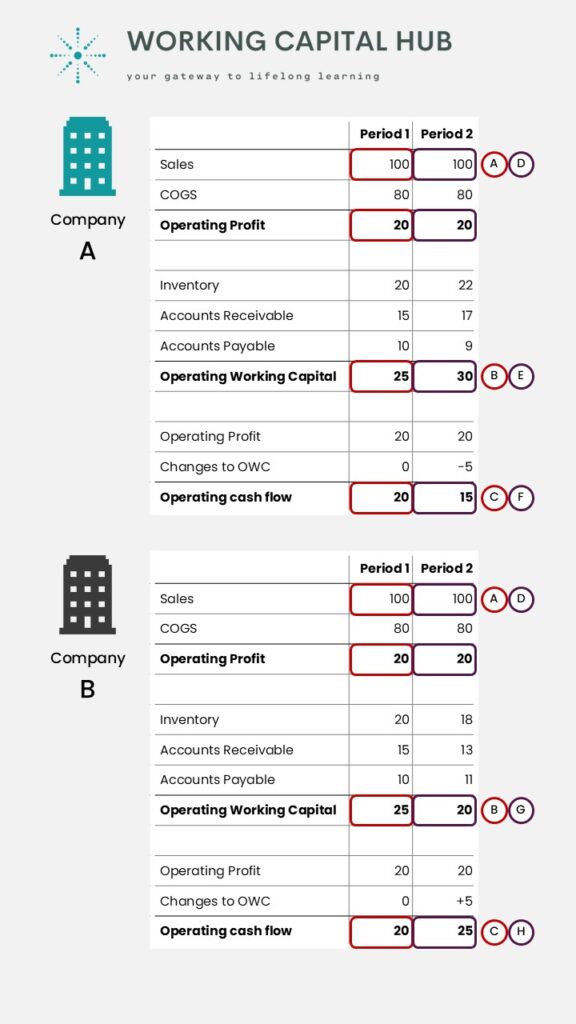

Consider two manufacturing companies (A and B) with the same financial performance in period 1.

- Both companies delivered an operating profit of $20m, from $100m in sales.

- Both companies carried net operating working capital of $25m.

- None of the companies saw any changes to its operating working capital from the previous period. This helped deliver an operating cash flow of $20m (20+/-0).

However, in period 2 we see some changes happening. - Sales and operating profit were at the same level as period 1 for both companies.

- However, company A experienced an increase in its operating working capital in period 2. This was due to external factors, increasing OWC from $25m to $30m.

- The increase of company A’s operating working capital of $5m had a negative effect on the company’s cash flow. This is because additional capital was tied up in operations.

- Meanwhile, company B actively worked to reduce its operating working capital requirements across the year, moving from $25m to $20m.

- The decrease of company B’s operating working capital of -$5m had a positive effect on the company’s cash flow, as less capital was tied up in operations.

Changes in operating working capital can have a significant impact on companies’ cashflow. In our example, company B had at the end of the second period $10m higher cash flow from operations, which could be used to invest in efficiency, growth or paying off debt.

Eager to learn more? Check out our accredited e-learning course Managing Working Capital

Leave a Reply