Operating Working Capital and the Cash Conversion Cycle

This article explains what the Cash Conversion Cycle is, what it consists of, and why it is important to understand.

It will also provide insights into how capital can be tied up in operations, and how this affects the balance sheet and a company’s cashflow.

Additionally, the article will also cover why there is no single definition of what a ‘good’ or ‘bad’ cash conversion cycle is, but rather depends on the type of industry and supply chain set-up.

Key Take Aways

- The Cash Conversion Cycle (CCC) metric looks at how effective a company is in managing its operating working capital.

- The shorter the cycle, the quicker a company can convert its invested Operating Working Capital into cash.

- The CCC encapsulates three key stages of a company’s operating cycle: the selling of current inventories, the collection of cash from current sales, and the payment to vendors for goods and services purchased.

- The CCC is calculated as Days Inventory Outstanding (DIO) + Days Sales Outstanding (DSO) – Days Payable Outstanding (DPO).

- The Cash Conversion Cycle is measured in days and should be evaluated against a company’s optimal level of operating working capital, its trend, as well as in comparison with relevant industry peers.

- CCC will differ by industry sector based on the nature of business operations.

“The cash conversion cycle (CCC), also called the net operating cycle or cash cycle, considers how much time the company needs to sell its inventory, collect receivables, and pay its bills“

INVESTOPEDIA

What is the Cash Conversion Cycle?

The Cash Conversion Cycle (CCC) can also be referred to as the Operating Working Capital Cycle or the Funding Gap.

It is a metric that tells how many days a company’s operating working capital is tied up in operations before being converted into cash.

This metric looks at the time needed for a company to sell its inventory, the time required to collect its customer receivables, and the time allowed to pay its supplier bills without incurring any penalties.

Learn more about how cash can be tied up in operations – take our accredited e-learning course Managing Working Capital on MyAcademyHub.com!

How can Cash be tied up in Operations?

When discussing how cash can be tied up in operations, it’s important to understand the concept of operating working capital.

Operating working capital refers to the funds a company requires and must finance to support its day-to-day operations. These operations include the procurement of raw materials, production processes, inventory management, and accounts receivable handling. Read more about Operating Working Capital here.

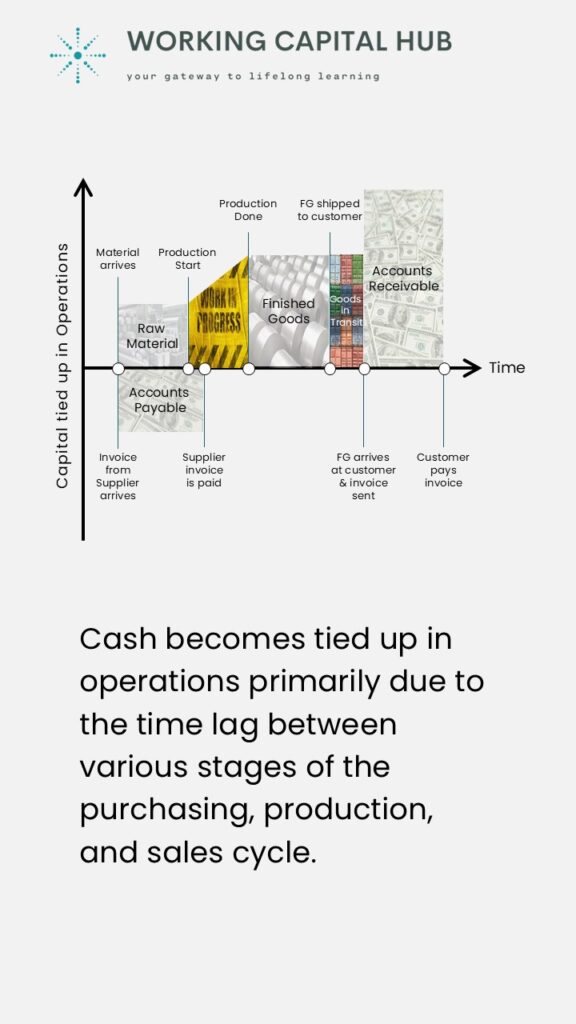

Cash becomes tied up in operations primarily due to the time lag between various stages of the purchasing, production, and sales cycle. Let’s break down these processes:

- Procurement of raw materials: When a company purchases raw materials from suppliers, cash is tied up in inventory. This cash is essentially locked into the form of materials until they are processed into finished goods and ready to be sold.

- Production processes: Once raw materials are acquired, they undergo processing and manufacturing, during which additional cash is invested in labor, equipment, utilities, and other overhead costs. This capital remains tied up in the form of work-in-progress inventory until the goods are completed.

- Inventory holding: After production, finished goods are held in inventory until they are sold to customers. During this time, cash is tied up in the form of finished goods inventory, which cannot be readily converted back into cash until a sale occurs.

- Sales and accounts receivable: Upon selling the finished goods, the company generates revenue. However, cash may still be tied up in the form of accounts receivable, as customers often require time to pay their invoices. The longer the payment terms or the slower the collection process, the more cash remains tied up in accounts receivable.

Overall, the entire cycle from procuring raw materials to receiving payment from customers represents a period during which cash is tied up in operations.

A certain level of operating working capital is required to effectively sustain the ongoing operations of a business. However, it is important to understand what this level is, as excessive levels can pose challenges, especially if the company faces cashflow constraints or operates with thin profit margins.

The Cash Conversion Cycle and Time

Time and Capital are closely interlinked. The cash conversion cycle is therefore not expressed as an absolute value, but rather as time, specifically days. Let us look at what we mean by this.

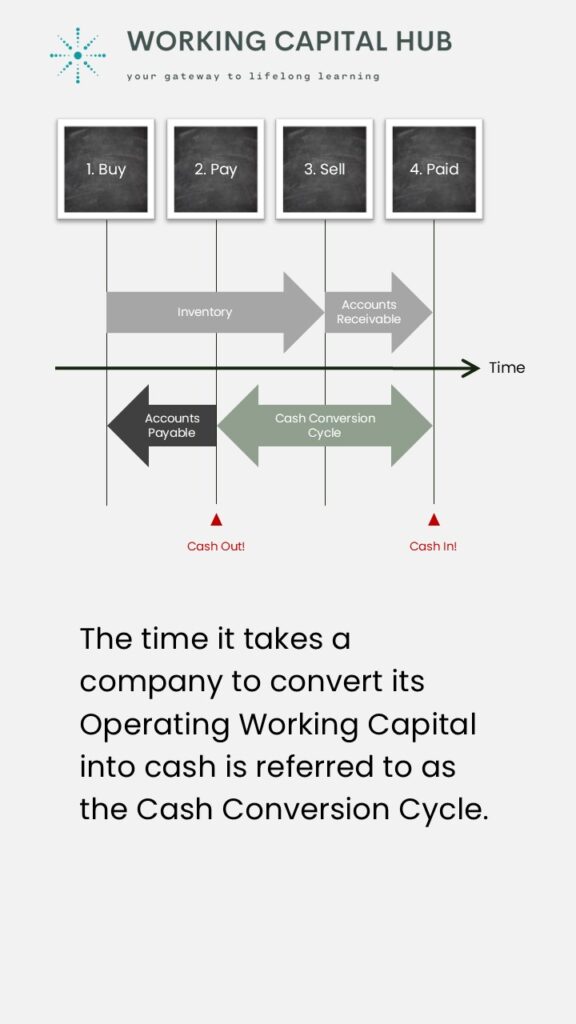

Imagine a timeline with four main events. A company Buys material for processing into sellable goods; it Pays its suppliers for the material received; it Sells products to its customers; and finally, it receives Payment for the products sold.

Firstly, we have the Inventory Account.

As soon as a material has been bought and processed, it sits in the company’s inventory account until sold. The length of the arrow, or the time the material is held on the inventory account, depends on how long the material is kept on the shelves before being sold to a customer.

Secondly, we have Accounts Payable.

When material is bought on credit, the company won’t pay until after the agreed supplier credit period reaches its end. The length of the arrow will reflect the credit time given. Say 30 days as an example.

Until the end of the credit period and payment is made, the value of the material is held on the accounts payable account. It is not until the credit period is over and actual supplier payments are made that cash outflow occurs.

Thirdly, we have Accounts Receivable.

When the customer buys on credit, payment is not made until after the credit period has ended. As with account payables, the length of the arrow reflects the credit time given.

When sold and invoiced, a product will leave the inventory account and the corresponding value will move to the accounts receivable, until the credit ends, and payment is made. It is not until the credit period is over and customer payments are made that cash inflow occurs.

The time it takes a company to convert its operating working capital into cash is referred to as the Cash Conversion Cycle. This is how long a company must finance the operating assets it has tied up in operations. This time can also be referred to as the Funding Gap.

How is the Cash Conversion Cycle calculated?

The CCC encapsulates three key stages of a company’s operating cycle:

- The selling of current inventories.

- The collection of cash from current sales.

- The payment to vendors for goods and services purchased.

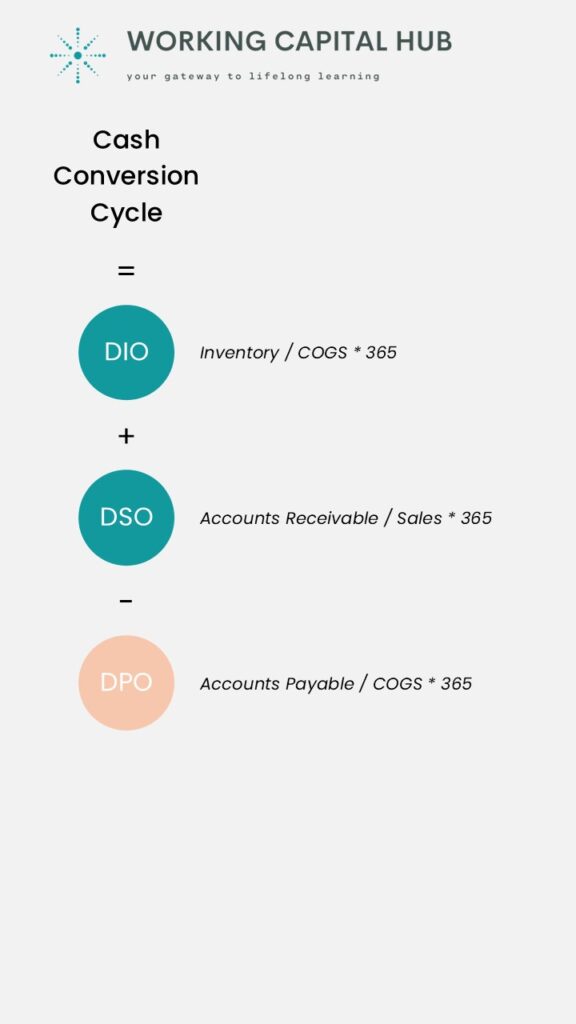

The CCC is therefore calculated using three other operating working capital metrics: Days Inventory Outstanding (DIO), Days Sales Outstanding (DSO) and Days Payable Outstanding (DPO).

DIO and DSO are short-term assets, while DPO is classed as a liability.

CCC = Days Inventory Outstanding (DIO) + Days Sales Outstanding (DSO) – Days Payable Outstanding (DPO)

Where:

DIO = Inventory / Annual cost of goods sold (COGS) x 365

The Days Inventory Outstanding metric is a measure of how many days on average a company holds inventory before sold.

DSO = Accounts Receivable / Annual Sales x 365

The Days Sale Outstanding metric is a measure of how many days on average a company takes to receive payments for its sales.

DPO = Accounts Payable / Annual COGS x 365

The Days Payable Outstanding metric is a measure of how many days on average it takes a company to pay its suppliers.

Interpreting the Cash Conversion Cycle

The cash conversion cycle metric looks at how effective a company is in managing its operating working capital.

The shorter the cycle, the quicker it can convert its invested operating capital into cash, through selling off its inventories, receiving payments from customers, while paying suppliers in a timely manner.

The cash conversion cycle will vary considerably between industries and could even vary between companies within the same industry.

This depend on differences in the respective company’s supply chain setup. There is no single definition of what a ‘good’ or ‘bad’ cash conversion cycle is.

- Each cash conversion cycle component (DIO, DSO and DPO), should be evaluated against a company’s optimal level of operating working capital – its Setpoint. Read more about lean operating working capital and a company’s Setpoint here.

- CCC should also be tracked over time to identify trends: if a company’s operating working capital is deteriorating or improving.

- Also, CCC can be used to compare companies operating in the same industry. However, as always when it comes to benchmarking, this should be approached with caution. Read more about benchmarking working capital here.

How to Improve the Cash Conversion Cycle

Effective management of working capital is crucial for ensuring the smooth functioning of operations and maintaining financial stability.

Strategies such as optimizing inventory levels, negotiating favorable payment terms with suppliers, improving accounts receivable collection processes, and efficient production scheduling can all help minimize the amount of cash tied up in operations and improve overall liquidity.

Strategies to reduce a company’s cash conversion cycle could include:

- Optimize Inventory Management: Keep inventory levels optimized to prevent overstocking or stockouts. Align system applied target inventory and safety stock requirements to demand profile and required service levels. Implement demand-driven or just-in-time inventory systems to reduce excess inventory holding costs.

Actively work to reduce slow-moving or obsolete inventories, as these can take up space at the expense of in-demand high runners. - Streamline Customer Invoicing and Collection: Accelerate the collection of accounts receivable by sending correct and timely invoices and following up promptly on overdue accounts. Implement pre-dunning for habitual late payers. Actively work to reduce dispute resolution time.

Also, consider implementing stricter credit policies to reduce the risk of late payments or defaults. - Manage Supplier Invoice Receipt and Payments: Ensure swift and accurate goods receipt and system entry practices. Make sure applied payment terms are aligned with supplier agreements. Pay on time but also identify and avoid payments made earlier than the due date.

Also, for invoices due on a weekend, consider making the payment the following Monday rather than the Friday before, as no transfers will take place over the weekend anyways. - Improve Operational Efficiency: Streamline workflows, invest in technology, and train all staff to work more effectively. Enhance operational efficiency to reduce waste, re-work as well as internal lead-times. Identify and remove bottlenecks.

Ensure frozen production plans to maintain optimal sequencing. Shorten change-over and ramp up time. - Improve Sales Efficiency: Actively work towards favorable payment terms as part of all customer negotiations. Assist collection in cases of disputes or habitual late payers. Improve forecast accuracy and align demand and supply through active participation in Sales and Operations Planning processes.

Align forecasts with relevant planning horizons, and make sure they are presented in a format relevant for operations (in same unit as used for planning purposes). - Improve Purchasing Efficiency: Actively work towards favorable payment terms as part of all supplier negotiations. Also, weigh in implications of longer delivery lead times when selecting suppliers: understand the implications on inventory and cost of capital. Review current supplier agreements and identify suppliers with terms shorter than policies allow.

Ensure only approved suppliers are used and align service level agreements across the organization. Reduce complexity by consolidating the number of suppliers or purchased items to improve both terms and cost. - Monitor Working Capital & Cashflow: Regularly monitor key working capital metrics and ratios to identify areas for improvement and track progress over time. Include relevant leading metrics to allow for early recognition of inefficiencies.

Install working capital reporting and follow-up in relevant management meetings as a fixed agenda point. Assign ownership and accountabilities. - Set & Align targets Across Functions: Ensure relevant and achievable targets, aligned with the company’s optimal working capital levels. Balance targets across functions to avoid conflicting agendas, and local optimization at the expense of the total business.

Ensure working capital and cash are high on the management’s agenda and connected to relevant incentive structures. - Utilize Working Capital Financing: Explore various working capital financing options such as Supply Chan Financing (e.g., Receivables Financing, Approved Payables Financing, etc.). Ensure to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of financing options.

- Regularly Review and Adjust Strategies: Continuously monitor your working capital management practices and adjust them as needed based on changes in market conditions, business performance, or other factors impacting liquidity.

By implementing above strategies, a company will improve its working capital and strengthen its financial position, ultimately enhancing its ability to meet short-term obligations and support long-term growth.

However, it is important to recognize that a company’s cash conversion cycle cannot be viewed in isolation; it also reflects the interactions with suppliers and customers.

For example, when a company extends or delays payments to its suppliers, this will negatively affect the supplier’s cash conversion cycle by increasing their DSO. This could, in turn, create cash flow challenges for the supplier, potentially leading to future price increases or impacting on their ability to meet orders on time and in full.

Eager to learn more? Check out our accredited e-learning course Managing Working Capital

Leave a Reply